The Cedar and the Salmon

I’m Vi (Taq.Se.Blu) Hilbert, daughter of Louise and Charlie Anderson, from the Upper Scagit tribe, which is near Cedar Woolley near the Scagit River.

I’m Vi (Taq.Se.Blu) Hilbert, daughter of Louise and Charlie Anderson, from the Upper Scagit tribe, which is near Cedar Woolley near the Scagit River.

The cedar and the salmon. People in our culture, the salmon were people. Each species was known to come and go at certain times and they were honored for the lives that they gave to my people for sustenance. They were honored in song and prayer. They were spoken to as if they would understand everything that was said to them because everything that has a life also has spirit.

We speak to the spirit of each of these things. We speak to the spirit of the salmon. We speak to the spirit of the tree and we know that these things are understood because we’re speaking to the spirit. We’re not speaking to the thing itself because the tree is wood. It has life. Every part of the tree is valued from the root to the bark to the way a cedar gives its’ life and can be split up to create many, many things.

So we knew how to use each of these things and to not waste them. The things that were given to us were not wasted. That’s what I grew up knowing about and I still see that surviving. That lesson continues to be taught. You don’t waste. You respect and use the things that are gifted to us by our Creator.

Each gender had responsibility. The woman, if she had been properly taught, knew how to handle everything that was in her domain to take care of. Her women’s family members taught her this so that they could be proud of her when she married and went to another family. She was taught never to be lazy, to always be industrious, and to continue to learn how to do new things.

You knew you’d been taught from day one how your people took care of the food. You learned from many other people how they were taught to take care of food and to prepare it, to serve it, to enjoy it.

But the woman knew what her place was and she could also go off and help the man in the food gathering if there was a scarcity of food and she was needed to go out and do what a man usually did. She was not above doing man’s work too. That was expected of her. The stronger the woman, the more she was respected. The more industrious she was, the more she was honored.

The man was expected to be a good provider, to be a good hunter, to know the land, to know where to find things on the land or where to find things in the mountains. The families went as a group to pick berries in the mountains, to pick berries in special berry patches and a woman had to know how to preserve those things, but the man had to know how to protect the family as they went out to do this because they were in competition with some of the animals. The bear was fiercely going to guard his source of berry fields and so the father was there to make sure the family was protected from the animals who needed food also.

The man was the hunter. The man was the provider of the game and either men or women knew how to fish for salmon. They knew where the best places were and they knew how to catch fish in different ways, in the creeks, in the rivers, in the deep eddies, and in murky muddy water. They knew how to find and catch those salmon wherever they happened to be hiding.

My grandfather, my dad’s father, was an expert at that and taught my dad all the skills of knowing the river and knowing how to use the river in every way so I had lots of respect for my dad’s knowledge of the water. It was wonderful to see him understand how the water worked and how to use each body of water, the still water, the rough water, and the quiet still water. I watched him read the river, read where the deep eddies might hold a special group of salmon. I think he could spear them without seeing them. He knew where they were and also where there was a big logjam and a particular way the water gathered around a logjam. He knew how to walk out on that logjam and find a salmon in the deep eddies that were created by the logjam.

I watched him do that as a child and I was allowed to travel with him. It was always a great joy for me to watch him at work and to know that I had to learn how to be very quiet, very still, never to jiggle the canoe, never to move, but to sit quietly and listen and observe. So that was part of my teaching, to learn how to be still, to learn how to listen. It was a beautiful childhood and I still appreciate that I was raised and given lessons of that kind and the patience that it takes to wait for things to happen. That’s why I guess I have a lot of patience.

My dad’s father had a longhouse on the Scagit River banks along with several other lean medicine men that also had longhouses. They were there always. They were made of cedar planks that had been taken from trees that had fallen and could be split into planks so that these plank houses had removable roofs made of the shakes from the cedar. These were the longhouses that held five or six or seven families, as many families as could live in an eighty, ninety, hundred and twenty-foot longhouse. People lived together and partitioned for privacy with cattail mat partitions or woven partitions of some kind so they weren’t soundproof, but people learned to live together in a communal kind of living. They cooked together and ate together.

There were times when it would be food-gathering time. They had temporary homes that could be constructed on the spot, and they would carry that material with them, cattail mats or woven pieces of the wall so to speak. They could use cedar branches for their floor, cedar branches to help ward off the rain and they knew how to construct things from the materials the Creator made available for them to use. They were temporary homes and they were movable homes for berry picking, for salmon gathering, or just for fellowship.

Sometimes people loved to be together so they would know that people were all gathering at a certain place, here, there, or somewhere else. They’d load everything into one or two canoes and move so they could be with other people to prepare for winter and preserve the food that was available in different places. They would go to the mountains for berries. They would go to the ocean for seafood. They would go out in the meadows for roots and things that were available that they had been taught over the centuries to use.

It was a very sophisticated society that my people were a part of because they knew how to use the land and they knew what was available for medicine, for food, for health, for sedatives because there were no drug stores. They had to know how to use the things that were part of the gift from the land and they had known this for centuries because this was all there was. The Creator gave that information from one generation to another.

Oh, the seasons, the seasons. There was a time for everything. In the summertime, of course, was the harvesting of food. It was also a time for fellowship, the kind of fellowship that was fun, which could be enjoyed in weather that was warm and comfortable to use. People gathered to play games together, to have fellowship that was separate from work. They combined work with fun always, a little bit of work, a little bit of fun, but they used the summer months mainly for the burying and for the specific salmon that were running during the summer months.

They knew the food cycles of everything that was usable for us and these food cycles were important to be completely aware of. In the winter months, because you had already prepared for the winter months, you had plenty of food. You always had a supply of wood available to you, because you would have gathered fir bark, which was our coal. Fir bark was very thick and would burn for a long time and give lots of heat. So we know all the wood that was available for use. We used the downfalls; the trees that had fallen because of age or the wind had blown them down. We used those and if there weren’t any trees down then we found a way to fall the trees without hurting another tree. The men were very skilled woodsmen. I watched how they would decide which way a tree would fall so it wouldn’t hurt another tree and make as little damage as possible because they knew how to get it to go where they wanted it to go.

The seasons were utilized for the gifts that the seasons gave us. When the weather was quite miserable, cold and snowy, icy, then the people would gather in the longhouses and be warm and well-fed because they had prepared for that time. This is a time for our spiritual practices that were honored among all of our people. They were given ways to understand how to contact the Spirit and knew that everything that had life also had Spirit. They were given this knowledge and taught how to use that Spirit possession in the proper way and how not to use it in an improper way, and the consequences if you used it improperly; and how you respected the gifts from the Spirit and you honored these gifts in a way that would enrich the Spirit and thus enrich yourself.

I watched this because I was born in 1918 and there was a lot of it still going on. I was taught to sit quietly and listen and never disturb other people who were the ones practicing the spirituality of all of our people. I was taught proper conduct at all times. Even though I was an only child, the rules were very strict for me to conduct myself so I would always be above reproach, that I would never, ever bring shame on any of my people by doing something that was not proper and to this day I abide by those teachings, never to bring shame on the people that gave me life.

Rivers are our highways. We had to be familiar with where the river started and ended. The current of the rivers and tides could help us to go where we needed to go. Without maps, we knew how to find our way everywhere that was important for us to be. The canoes were built for specific water. Canoes were built for quiet water, lake water, river water, for saltwater. The people were so intelligent that they knew what was right for each place and from experience over the hundreds and hundreds of years that they had to do this, using primitive tools that they had learned to create for this work.

I watched my Dad carve canoes. He carved river canoes; race canoes and carved little hunting canoes. He did not carve sea-going canoes. That was a job for somebody else because my dad was a riverman, not a salt-waterman. My mother’s people were a saltwater people. She knew how to deal with saltwater better than my dad did. Her grandmother raised her on saltwater. My dad was raised on the river.

The first psychiatrist of this land, our medicine men, used the simplest things. They realized how important acknowledgment was. If a person was to rise to the highest goal that their families expected them to practice and if their deeds and accomplishments went unnoticed, why should they try? Why should they do anything? Nobody paid any attention to that anyway. Our medicine men knew that this was very important. If you could see somebody doing a great piece of work at great hardship to him or her, then you pointed that out. You paid attention in public for the great thing you had just seen accomplished by this person. What a wonderful job this person was able to do because somebody had taught them how to use their hands and their mind and their eyes in a good way. They would give credit to the teacher and to the student. Everyone was acknowledged for having a part in this great work that was being done because this person had been able to learn about what was important. So this is acknowledgment. It’s a medicine used by the greatest of our medicine men, because if you sit in a roomful of people and you go unnoticed forever, why should you come to be with any of the people who are there. Nobody knows that you’re there. Nobody cares that you’re there. Why should you be there to learn anything? So that person might have a medicine man sense the sadness in your heart that nobody ever paid any attention to. Nobody ever notices that you even exist. The moment a medicine man points out to the houseful of people that you are there and you have been seen to do this. You have been acknowledged for the gifts that you yourself have given and then you are known then you feel good about who you are because somebody has paid attention to what you do and who you are. Acknowledgment is the best medicine that could ever, ever be practiced.

Spirits exist wherever there is life. Water is alive. The river is alive, the rocks on a river bed, the sand along the banks of a river. Everything that’s contained in a river has life and because it has life, it also has spirit. I have repeated that several times. If it has life, it also has spirit. My people also know this. When they are sent for spiritual help, they know that if they are successful, they will be recognized by the spirits that are part of the water, a part of the rocks, a part of the movement, a part of anything that lives and breathes with the water.

So these are things that our people have always been taught in a very subtle form, never in the words that I’ve been using to talk to you who haven’t had the advantage of being taught from birth that these things exist and can be used. For instance, the subtlety of information that is known to us is so abstract sometimes that the abstractness gets lost to people who don’t have minds who are able to accommodate the abstract.

Do you know that sound is a spirit? The sound of something happening is a spirit. It’s too abstract for most of our minds to accept. The sound of two trees rubbing together is a spirit. It’s too abstract for us to really accept it as a source of spirit. The sounds of a hurricane, these things are part of the abstractness of the culture.

The most valuable thing I know of to do during my lifetime is to try to find some way to help my people. How do I know what kind of help they need? I know because I watch them and I listen to them. I know that they are lacking in lots and lots of information because they haven’t had time to live the culture as I have lived it.

Unfortunately, I have observed that my young people feel just because they are members of the longhouse winter spiritual gatherings that that’s all they need to know to honor the culture and I know that is not true. It’s important to honor the spiritual practices of my people, but that’s only a very small portion of it. If they are to take their proper place in the culture, then that’s a foundation that in the old days came as a stepping stone to the education that they would need help receiving.

So if indeed that is true, becoming members of the winter spiritual season that has talked on the discipline that’s needed in order to learn about the importance of all facets of your culture and how to find that information is a job that their spiritual help will help them to attain. So, in the old days, spiritual help was a gift that you had to earn in order to make your life better, to make your life stronger, to allow you to live honorably in this world because you had the help of the spirit. This is what the young people have mistaken as the entire thing. It’s just a part of it. It’s a stepping stone to becoming educated. It’s a degree, a college degree if you will. It’s not a graduate degree. It’s a college degree for them to become a doctor in the culture.

I’ll be doing things to try to help my people maintain their culture, maintain the law and knowledge of their culture, and for those who have time to let them listen to their language and listen to their stories and know if they really want to learn. They can learn from the first textbooks that were prepared by our people and those were the stories. The literature of the culture is where everything is maintained, the history, the humor, the philosophy, the teachings are in the legends, in the old stories that were left by my people.

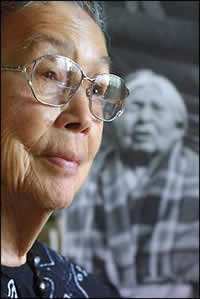

Vi Hilbert

The late Vi Hilbert, whose Indian name is Taqwseblu, was a member of the Upper Skagit tribe. Her life’s work was preserving the Lushootseed (Puget Salish for “Puget Sound, connected to the saltwater.” ) language and culture. Vi learned Lushootseed, the language of Chief Seattle, as a child listening to her parents. She was widely acknowledged as a respected elder, tribal historian, linguist, and storyteller.

Vi has co-written Lushootseed grammars and dictionaries and published books of stories, teachings, and place names. She generously shared Lushootseed language, stories, and traditions with organizations such as the Burke Museum, the Seattle Art Museum, United Indians of All Tribes, Tillicum Village, Seattle Storytellers Guild, and the National Storytelling Association. Vi taught Lushootseed to every audience she addressed, especially traditional gatherings so that this ancient language could be heard throughout Puget Sound where it has been spoken for centuries. Through her years of work, Vi has collected, transcribed, translated, and documented materials that include: the Leon Metcalf Collection (the 1950s), the Warren Snyder and Willard Rhodes collections (1950s), Arthur Ballard’s collection (early 1900s), T. T. Waterman’s Puget Sound Geography (1910s), and the Thomas Hess material (1960s and 1970s). Her recollected knowledge also allowed her to help linguist Thomas Hess transcribe and translate early Lushootseed recordings of elders.

Vi insisted that she was not only a storyteller but a channel for cultural information. When she attended the gathering and observed that a particular story needs to be heard, she would stand and tell that story. When invited to speak, Vi never planned ahead what she would say or what stories she would tell. She would arrive early to listen to her audience and see whether they would need to hear the exploits of Skunk, Mud Swallow, Mink, Coyote, Deer, Bear, Ant, or other animals. She was named a Washington State Living Treasure in 1989. She also received a National Heritage Fellowship from National Endowment for the Arts, the first American Indian storyteller to be acknowledged with this high honor.