My People

My name is Curley Youpee. I’m a Minicoujou, Hunkpapa; Lakota and Pabaksa Dakota. I live on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Poplar, Montana. My ancestors came to Montana as a result of the Dakota uprising in Minnesota and also the unfulfilled treaty obligations, which brought on starvation of the people on the reservations of Cheyenne River and Standing rock.

My name is Curley Youpee. I’m a Minicoujou, Hunkpapa; Lakota and Pabaksa Dakota. I live on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Poplar, Montana. My ancestors came to Montana as a result of the Dakota uprising in Minnesota and also the unfulfilled treaty obligations, which brought on starvation of the people on the reservations of Cheyenne River and Standing rock.

My grandmother on my father’s side was called Big Woman. She was the wife of Black Moon. Chief Moon was one of the Hunkpapa during 1870. Her mother who escaped the Wounded Knee Massacre was called Na ke hi hi na in 1890. Her son Black Coyote and her son Dogskin Necklace died at Wounded Knee. Her son Black Coyote is the one who wouldn’t give up his rifle, which they claim had started the whole fight at Wounded Knee. We got a lot of different sides of that version. I guess as far as having any folks in the history books that would be them including Owl Bull who was Na ke hi hi na’s husband and father of Black Coyote. Dogskin Necklace, Long Horn, and Looking Thunder all signed the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty at Fort Rice when Father Desmitt was taking that treaty around for signatures as well. He signed the treaty with Sitting Bull, Owl Bull, and Running Devil at Fort Rice.

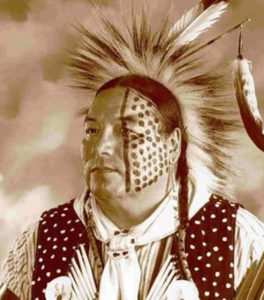

Curley Youpee (Sung’ Gleska), Lakota Horse Dreamer

Lakota Horse Dreamer, Curley Youpee – Sung’Gleska, is a fifth-generation activist for Indigenous rights and environmental protection. He grew up on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeast Montana. His approach to reducing racial hatred and social injustice against his people has earned him a seat in human rights circles and won him national recognition among US government organizations such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Bureau of Land Management, and Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs. “It’s a matter of finding peace. Learning synergy through non-adversarial, action orient strategies,” declares Mr. Youpee.

Lakota Horse Dreamer, Curley Youpee – Sung’Gleska, is a fifth-generation activist for Indigenous rights and environmental protection. He grew up on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeast Montana. His approach to reducing racial hatred and social injustice against his people has earned him a seat in human rights circles and won him national recognition among US government organizations such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Bureau of Land Management, and Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs. “It’s a matter of finding peace. Learning synergy through non-adversarial, action orient strategies,” declares Mr. Youpee.

As Cultural Resources Department Director of the Fort Peck Tribes, Mr. Youpee coordinates cross-cultural training and presents the historical and cultural backgrounds of the Assiniboine and Sioux people. Concerned with the loss of tribal culture, he started collecting oral history in 1982 to assemble the Tribes’ principal audio/visual collection.

His great-grandmother, Father’s Big Woman, was the youngest wife of Chief Black Moon (Hunkpapa) in 1870. Her mother Na ki hi hi na narrowly escaped the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Na ki hi hi na‘s sons, Black Coyote and Dog Skin Necklace of the Minicoujou, were among those killed during the Wounded Knee collision. Mr. Youpee clarifies that Black Coyote, akicita (police) for his people, fought with soldiers trying to confiscate his rifle. “He wasn’t allowed to give up his gun,” explains Curley, “because his Akita responsibility was the only protection left for his people.” Many dispute this incident as the cause that led to the deaths of 300 men, women, and children. “It is clear that the Lakota wanted to minimize additional backlash from the US military so they conjured up a scapegoat,” defends Mr. Youpee.

Black Coyote’s father Owl Bull; a Hunkpapa, and brother Long Horn; a Minicoujou, were signers of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. After the loss of the Great [Sioux] Reservation, the Lakota under the leadership of Black Moon and Sitting Bull began to resist confinement under proviso rule. Band by band, the Lakota deserted their reservation quarters to live among the Yanktonai, who had settled on upper Missouri subsequent to the 1862 Dakota rebellion in Minnesota. In 1875, upper Missouri Dakota and Nakota delegates were brought to Washington DC by US Indian Commissioners to formally negotiate a reservation of their own. Eventually, a 2.2 million-acre Reservation proposition was ratified in 1888 by Congress for both the Sioux (Dakota, Lakota, Nakota) and Assiniboine (Nakoda) people. Intermingled and intermarried, today 3 bands of the Nakoda and vestiges of 56 bands of the Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota make up the Fort Peck tribal population.

He lectures across the country using the history, traditional beliefs, and storytelling of the Assiniboine and Sioux people. He shares the legend and creation stories of his people. “Creation comes from the universe and brought down in sacred deities,” explains Curley. The Iktomi (Trickster) stories of the Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota teach children discipline and morals. He has a story of how the Upper Yanktonai got their name Cuthead (Pabaksa).

He wants to pass on to the children these teachings of the tribe’s history, culture, traditions, and language. His audiences are diverse in age from young to elders. Curley’s interpretation of his people and heritage stems from his experience with real people on lands they hold sacred. Emanating from the upper plains and its land and people, the stories not only have authenticity but also are connected to the strength of their subjects. He credits his elders as mentors for bringing him this far. “They knew me when I didn’t know them. As a child, elders would talk to me like I understood everything they were speaking about. Those encounters left me deep in thought and feeling alone. It’s like I was this adult who had all of these old friends,” he explains. They gave him their time and time is invaluable.

Mr. Youpee is also a talented artist who brings together carved symbolic horses and dramatic imagery in a traditional abstract manner, achieving an illusory, mysterious effect that connects the viewer’s imagination. In addition to being collected by museums, Curley’s horse carvings are displayed throughout the northern plains region at popular galleries and gift shops.

Curley Youpee

PO Box 836

Poplar, MT 59255

406-768-5559

0c0y01@nemontel.net